Exhibition: The Swanzy Riots, 1920

Introduction

This exhibition explores one of the most difficult episodes in Lisburn’s recent past: the Swanzy Riots of August 1920. The assassination of R.I.C. District Inspector Swanzy on a quiet, sunny Sunday in Lisburn led to days of vicious looting and rioting, forcing many of the town’s Catholics to flee. While a significant, but not well known, event in Lisburn’s rich history, the Riots are part of the wider story of the War of Independence (1919-1922) on the island of Ireland.

This exhibition features, for the first time, a database of 300+ compensation claims relating to the Riots, and an interactive map developed in conjunction with local historians, Pearse Lawlor and Pat Geary, and Charlie Roche (University College Cork/Atlas of the Irish Revolution).

A list of acknowledgements and suggestions for further reading can be found at the end of the exhibition.

British Pathe, The Irish War of Independence

Life in Lisburn, 1920

On the eve of the riots, what was life like in Lisburn?

Lisburn was a busy, industrial town famous for its connection to the linen industry. In 1920 the community was still reeling from the Great War (1914-18), in which almost 1000 local men and women had lost their lives. For those who returned home, life was hard and job prospects were limited.

Lisburn Urban District Council (L.U.D.C.) was responsible for the town’s amenities and services, and just over 12,000 people lived within its boundaries. Law and order was upheld by the Royal Irish Constabulary (R.I.C.), with barracks on Railway Street, Smithfield and Hillhall.

Local politics were firmly unionist, although the electorate had been scandalised in January 1920 with the election of the first Sinn Féin councillor to Lisburn Urban District Council (L.U.D.C.), William Shaw. Community relations were good, although tensions were easily roused at times of political conflict.

Postcard, Lisburn RIC at the Temperance Institute, c. 1900

ILC&LM Collection

Lisburn RIC gather outside the gym and social rooms on Railway Street.

The Irish War of Independence

On 21 January 1919, the First Dáil met in Dublin and declared Irish independence. On the same day, the opening shots of the Irish War of Independence (1919-21) were fired in Tipperary, claiming the lives of two R.I.C. constables.

The War was fought on several fronts. Soldiers and police were refused carriage on trains or service in shops, and independent Dáil Courts were established to undermine the state. The R.I.C. were frequent targets in an increasingly bloody guerrilla war waged by the Irish Republican Army (I.R.A.). Across the country, barracks were raided and many ‘Old R.I.C’ men resigned. Police ranks were bolstered in early 1920 with almost 10,000 ex-soldiers, the ‘Black and Tans’, followed by a special counter-insurgency force, the Auxiliary Division.

County Cork was the most violent county in Ireland during the war of independence and Cork City, the county town, saw much of this action. In January 1920 Tomas MacCurtain (1884-1920) was elected the first Sinn Féin Lord Mayor of the city. A prominent local businessman, MacCurtain was head of the No. 1 Brigade of the Cork I.R.A. He was known as a moderate and often clashed with more violent elements within the Brigade.

Christmas Card, The New RIC, c.1920

by kind permission of the Police Museum, Belfast

A Regular R.I.C. Constable (left), ‘Black and Tan’, and Auxiliary Division Cadet (middle). Both units were responsible for ‘reprisal’ attacks. The Cadets famously burned Cork in December 1920, while the Black and Tans – regular RIC constables – sacked Balbriggan and besieged Tralee, Co. Kerry.

Murder, Murder, Murder!

On 20 March 1920 Tomas MacCurtain was murdered at his home in front of his wife and children by unknown members of the R.I.C. in Cork. His death was a reprisal for the increased targeting of police in the city. Indeed, on the night MacCurtain was murdered R.I.C. Constable Murtagh had been shot dead by the Cork I.R.A.

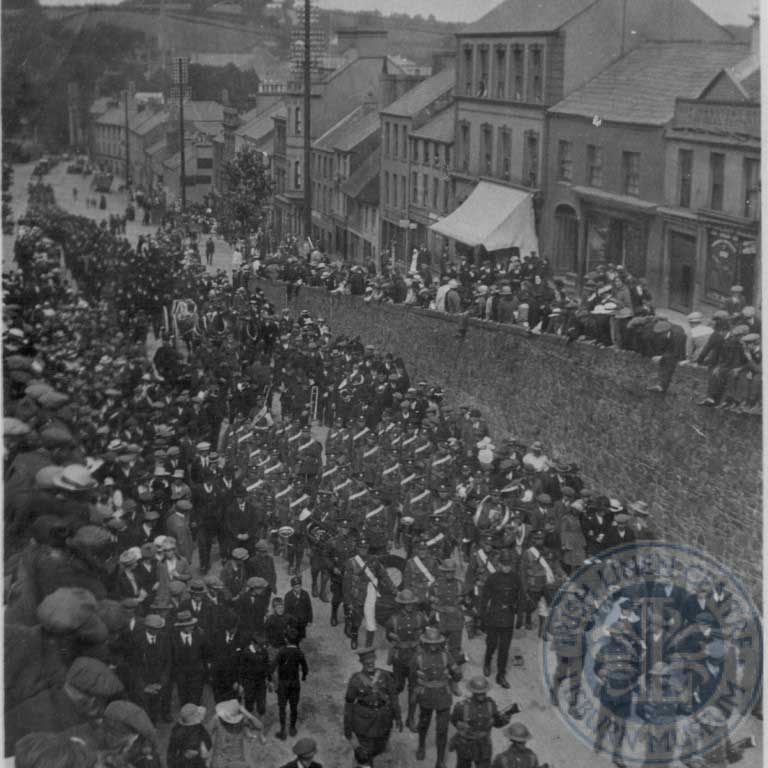

The public was outraged by MacCurtain’s murder and over 20,000 people attended the funeral, which was one of the largest Cork City had ever seen.

An inquest was quickly set up to investigate the circumstances of the Lord Mayor’s death. Over fifteen days an inquest jury sat in City Hall and heard sensational testimony that damned the local Police. Eyewitnesses placed men from King’s Street R.I.C. barracks, Cork City, in the vicinity of the murder, and the discovery of spent police cartridges and R.I.C. button at the scene points to a Constabulary rifle having fired the fatal shot. R.I.C. District Inspector Oswald Ross Swanzy was responsible for the North District of the city where the murder took place, and witnesses claim to have seen a man fitting his description talking to the murder gang shortly before the assassination. The jury heard that in the days that followed the murder, the R.I.C. made little effort to investigate the crime.

The Inquest

On 17 April 1920, the jury returned their verdict, finding that:

Alderman Tomas MacCurtain, Lord Mayor of Cork, died from shock and haemorrhage, caused by bullet wounds, and that he was wilfully wounded under circumstances of the most callous brutality; and that the murder was organised and carried out by the RIC officially directed by the British Government.

They famously returned a verdict of:

wilful murder against David Lloyd George, Prime Minister of England; Lord French, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland; Ian MacPherson, late Chief Secretary of Ireland; acting-Inspector General Smith, of the RIC; Divisional Inspector Clayton of the RIC; D.I. Swanzy, and some unknown members of the RIC.

After the inquest, the men suspected of involvement were under threat. In May 1920 R.I.C Constables Harrington and Garvey, who were believed to have fired the fatal shots, were gunned down by the Cork I.R.A., and King’s Street Barracks was destroyed. By mid-June 1920 D.I. Swanzy was in Lisburn, having been transferred for his own safety.

Newsreel footage of the Lord Mayor’s funeral, March 1920.

British Pathé

The Inquest Jury deliver their verdict.

Illustrated London News, April 1920

Object: Postcard, King Street, Cork c.1910

ILC&LM Collection

King Street was renamed MacCurtain Street in honour of the Lord Mayor. The barracks, from which the murder gang were alleged to have come from, can be seen bottom right.

A Long Hot Summer: East Ulster Ignites

The increasing violence of the Irish War of Independence in the south was matched by Sinn Féin success in the north. Tensions were rising as northern protestants felt increasingly under threat.

On 12 July 1920 Sir Edward Carson M.P. delivered a fiery speech to Orangemen at Finaghy, threatening to re-form the Ulster Volunteers. Five days later tensions increased with the murder of R.I.C. Divisional Commander for Munster Lt Col Gerald Rice Smyth (1885-1920), of the well-known Banbridge linen family, in Cork City. He was alleged to have advocated a ‘shoot now, ask questions later’ approach to Sinn Féiners when addressing members of the R.I.C. at Listowel, Kerry. The men famously mutinied.

Smyth’s funeral led to fierce rioting and attacks on local Catholics in Banbridge and Dromore, while in Belfast thousands of Catholics were expelled from the shipyards and other industrial works by loyalists.

In late July, disturbances spread across east Ulster, including Bangor, Newtownards, Antrim and Lisburn. Here the newly appointed D.I. Swanzy and several constables had to charge the rioters with batons as they wrecked shops and looted over 30, mainly Catholic, businesses, from Bridge Street to Chapel Hill.

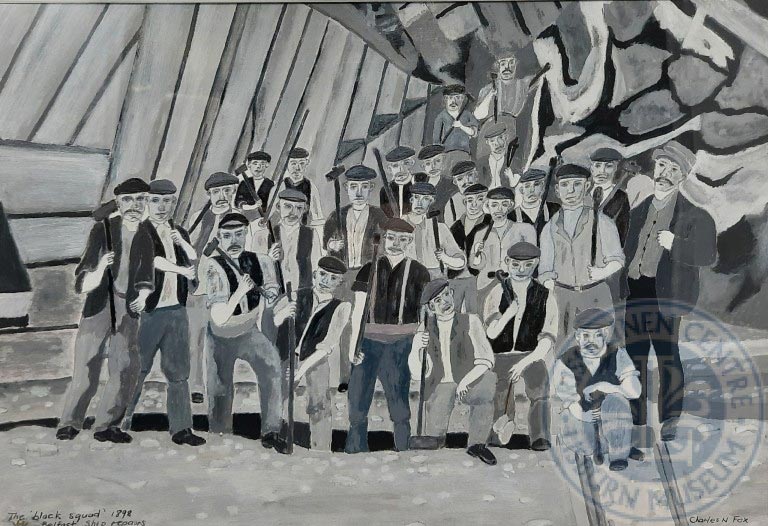

Object: ‘The black squad, 1898 Harland & Wolff’ by Charles Fox, Acrylic on Board

ILC&LM Collection

The Black Squad – platers, caulkers, welders and burners – were just some of the thousands of workers on the shipyards. The expulsions of July 1920 saw over 7000 Catholics and “rotten prods” (non-sectarian protestants) expelled.

‘Trouble in Lisburn’, headline in the Lisburn Standard following the 24 July 1920 riots.

Click to explore the newspaper report.

The Assassination of D.I. Swanzy

On 22 August 1920 Major Ewart, a Great War veteran, and his father Frederick Ewart, a wealthy linen industrialist, left Sunday service at Christ Church, Lisburn (on the Hillsborough Road) with District Inspector Swanzy. The men chatted as they travelled through Market Street and then north Market Square. But, as they turned the corner at Railway Street, where Swanzy lived at no. 31, the D.I. was shot at point-blank range behind the ear, and then again as he lay on the ground. He died instantly. The four gunmen – members of the Cork and Belfast I.R.A – ran to their waiting car on Castle Street, firing at the crowd who gave chase.

The assassination was revenge for MacCurtain’s murder, and the men allegedly used MacCurtain’s revolver to commit the crime. By a cruel twist of fate, the legal licence had originally been signed by Swanzy in Cork.

Sean Culhane, a Cork intelligence officer, fired the first shot at Swanzy. He had also shot at Lt Col Smyth in the Cork County Club in July 1920. And, just as Smyth’s murder brought violence to the streets of Banbridge, a riot followed Swanzy’s assassination in Lisburn. Travelling home on the Belfast to Dublin hours after the murder, Culhane recalled that ‘on the train passing through Lisburn we noticed a number of houses on fire’.

Lisburn was burning.

District Inspector Oswald Ross Swanzy, c. 1920

Illustrated London News

Born in Monaghan, Swanzy (1881-1920) was an experienced RIC officer, having served in Cork since 1917. He had previously been stationed in Limerick and Carlow.

A display in the Museum’s 1918-23 exhibition

The case included an R.I.C. D.I. Dress Jacket and Helmet (on loan from the Police Museum, Belfast), a photograph of Swanzy in uniform (from the Lisburn Standard) and a book given by the Rev H.B. Swanzy (1843-1932) – genealogist and Church of Ireland historian – to his brother, highlighting the entry (p86) to their cousin, D.I. Swanzy, ‘whose loved memory will not soon die in Lisburn’.

Lisburn Burns Once More

As news of Swanzy’s assassination spread a crowd gathered in Market Square. Their anger soon turned to violence, and they rushed Isabella Gilmore’s confectionery shop on Cross Row (Market Square East today) – directly opposite the murder scene – and looted and burned the premises. Gilmore’s sons were well-known ‘Sinn Féiners’. Next, the mob turned to McKeever’s Public House on Bridge Street. In the process of looting the premises, the publican was shot. On nearby Linenhall Street, the A.O.H Hall was burned, as was O’Shea’s and Connolly’s in Market Square. On Haslem’s Lane William Shaw, Lisburn’s only Sinn Féin councillor was badly beaten, and James Strong, a recent Sinn Féin candidate for the Board of Guardians, had the contents of his home on Bachelors Walk emptied and burned in the street.

This initial wave of rioting broadly targeted the handful of Sinn Féin activists in Lisburn and the town’s constitutional nationalists, notably through the A.O.H. Hall. But, as the day wore on, the rioters turned to the wider Catholic population, and swathes of Market Square, Bow Street and surrounding streets were looted and burned. Many protestant-owned businesses were also damaged.

The military was brought in from Belfast to protect St Patrick’s Church on Chapel Hill and the Convent on Seymour Street. As the Belfast News Letter remarked, there was a great deal of burning, arson and looting. Lisburn was like ‘an episode in Dante’s Inferno’.

On Monday morning Lisburn was quiet, but by the early afternoon fires had been set in and around the town. Soon, the Comrades of the Great War Club and Todd Bros’ public house on Market Square succumbed to flames and Donaghy’s Boot Factory was burned, having been looted the previous day. A body, believed to be a looter, was found in the smouldering ashes. Further down Bow Street, Redmond Jefferson’s yard was burned, and – in just one scene of many – looters could be seen hurling armfuls of goods out on to the streets, and casually helping themselves.

The violence reached a crescendo late on Monday evening. On one end of the town The County Down Arms on Hillhall was looted while, at the other, there were ‘wild’ attacks on Catholic homes in and around Chapel Hill and Longstone street. The parochial house off Longstone Street was set alight. Rioters allegedly ‘danced around in priests’ vestments’ as the house was raised to the ground.

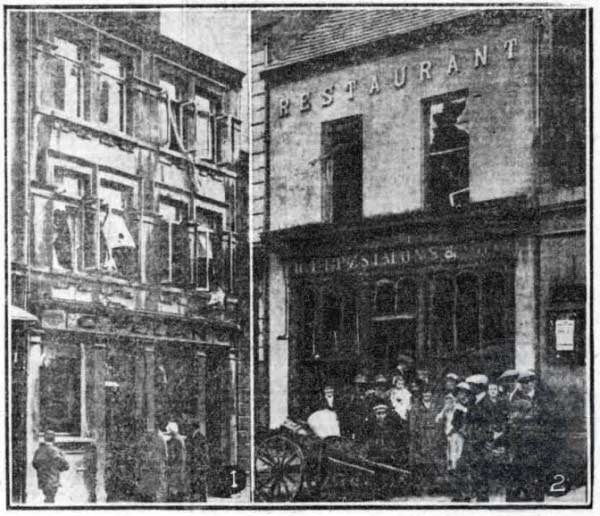

The scene of Swanzy’s Assassination (1) August 1920, and (2) today

ILC&LM and kind permission of Pat Geary

McKeever’s Pub, Bridge Street and the home of the Gilmores, Cross Row, Market Square

Larne Times

Video montage of the Riot damage

ILC&LM

Calm after the Storm

On Tuesday, 24th August, Lisburn was calm, although its commercial centre and outlying streets were devastated. It was likened to a ‘bombarded town in France’ during the Great War (1914-18).

As one Belfast newspaper reported, almost every home and business now flew a Union Flag, even the nationalists, as the ‘flag meant safety’. Some local mills and factories required employees, returning to work, to sign a declaration of loyalty. Several workers at Hilden refused and left the mill.

In response to the violence, L.U.D.C swore in ‘loyal’ special constables on August 30 at a meeting in the Assembly Rooms. The men patrolled and secured approaches to the town at night alongside the R.I.C. This force would eventually comprise over 800 men, although the R.I.C. later reported that the men considered themselves ‘Ulster volunteers more than peace officers’. The enrolment of Special Constables in Lisburn pre-dates the establishment of the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC), in October 1920.

During the disturbances, and in the days after, many Catholics fled the town. One eyewitness recounted how, ‘footsore and weary’, Lisburn Catholics headed for Belfast. It is estimated 150-250 families left Lisburn. Approximately 1000 people, around a third of the town’s Catholic population, were affected by the riots. Although many returned to the town, the local R.I.C. reported that 400 individuals were still absent from Lisburn in October 1920. There was a further flare-up of violence in late September 1920, with burning and arson in Railway Street, Quay Street and Gregg Street, although not on the same scale as the August Riots.

While the rioters had largely targeted the town’s Catholic population, victims came from all sides of the community. For example, James McKnight, a protestant from the Maze, wrote to the War Officer to request a replacement medal for his son who had died in the War. Having left the medal into a watchmaker to have a ribbon added, it was destroyed as Bow Street went up in flames.

Letter from the father of James Mcknight to the War Office, September 1921

ILC&LM by kind permission of Pat Geary

Object: frontpage of the Illustrated London News, Lisburn, ‘A scene suggestive of Ypres’, September 1920

ILC&LM

Evacuating premises, Bow Street, August 1920

Larne Times

Union Flags flying on Bridge Street, August 1920

ILC&LM

Aftermath and Justice

In the aftermath of the riots, almost 300 compensation claims for damage or loss were lodged. These amounted to around £850,000 (equivalent to 38 million pounds today), although only a fraction was paid out (around £206,000, or 9.2 million today). The new Northern Ireland government eventually paid the compensation claims.

Of the five men who set out to assassinate D.I. Swanzy on 22 August 1920 only the driver, Sean/John Leonard, faced charges. He was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death, although this was later commuted, and he was freed.

In Lisburn, very few of the rioters and looters were charged, and only a handful were prosecuted. Thomas Watson an ex-soldier from James Street (Smithfield), for example, was found guilty of burning Dornan’s on Bridge Street. His sentence of four months hard labour was later suspended on appeal, with his solicitor and the Crown prosecutor, Mr Moorhead, both agreeing that his actions had been a ‘temporary lapse’. In October 1920, after several of Lisburn’s special constables were charged with rioting and looting during the August disturbances, an angry crowd formed in Market Square and half of the town’s special constabulary threatened to resign unless their colleagues were freed.

Why did the authorities seem unwilling to prosecute rioters and looters? While some have viewed this as sectarian, others see appeasement reflecting a widely held view that the riots were simply a ‘moment of madness’. There was also a desire to keep the peace. As the War of Independence raged the north was becoming increasingly violent – there were 25 deaths in Belfast in the week following Swanzy’s murder – and after the riots, the authorities wanted to maintain the town’s fragile peace.

Mapping the Riots

This interactive map provides a visual overview, for the first time, of the extent of the rioting in Lisburn in summer 1920. The map draws on material from Pearse Lawlor’s 2009 The burnings 1920 (Mercier Press), and a database of 300+ compensation claims made in connection with the riots in 1920/21 and compiled by the Irish Linen Centre & Lisburn Museum.

The map is a collaboration between the Museum, Charlie Roche (MobileGIS, associated cartographer/researcher for University College Cork’s Atlas of the Irish Revolution), Pat Geary (local historian and author of the Lisburn and the Great War Research Project) and Pearse Lawlor, author of The Burnings 1920.

The map was designed and executed by Charlie Roche.

A full version of the map can be found here. The database of 300+ compensation claims is available here.

The Legacy of the Swanzy Riots

Lisburn was famously burned to the ground in 1707 after an accidental fire, but quickly rebuilt, with one traveller remarking ‘if the story of the Phoenix be ever true, sure ’tis in this Town’. Lisburn was, again, put back together in the years after the Swanzy Riots. By January 1922, when a new statue to the Victorian hero of Empire John Nicholson (1822-1857) was unveiled, Market Square had been restored to its former glory.

Yet, laying bricks is much easier than repairing community relations, and many local Catholics returning to the town entered – as a historian of the Riots Pearse Lawlor has described – a protracted period of ‘keeping their heads down’. The collective memory of the violence cast a long shadow. Indeed, locals still refer to ‘the burnings’, ‘troubles of the 20s’ or even ‘the pogroms’, although the use of this label to describe the violence has been fiercely debated by historians.

The day-time murder of Swanzy in the heart of unionist Lisburn was shocking, and revenge was acted out on the local Catholic community. A chain of events that began with the murder of the Lord Mayor of Cork ended up in violence on the streets of Lisburn.

The violence in the town was just one episode in a series of events. The disturbances that swept across East Ulster in summer 1920 reflected wider unionist fears around the threat to communal security, the uncertainties of partition and anxiety that the violence of the south was coming north. The disorder only escalated, and from 1920-22 east Ulster was the most violent region in Ireland, embroiled in a bitter sectarian conflict. The victims in this desperate sectarian feud were disproportionally civilian.

Acknowledgements

The Museum would like to extend thanks to Pearse Lawlor, Pat Geary and, in particular, Charlie Roche for their help and expertise in ‘mapping’ the riots. Pat Geary provided invaluable time and expertise in collating the database.

Thanks are also due to several individuals who provided help with research on various aspects of the story, including: George Scott, Dr John Borgonovo, Dr Eamon Phoenix, Prof Brian Walker and Dr Christopher Magill.

The Museum is grateful to Julie Casson (Corporate Communications) and Colin Breadon for help with the featured video.

Suggested Further Reading:

John Borgonovo, Florence and Josephine O’Donoghue’s War of Independence: A Destiny That Shapes Our End (2006)

Kieran Glennon, From Pogrom to Civil War: Tom Glennon and the Belfast IRA (2013)

Pete Hart, The IRA and its enemies: violence and community in Cork, 1916-1923 (1998)

Pearse Lawlor, The Burnings (2009)

Brian Mackey, Lisburn, the Town and its People 1873-1973, (2000)

Christopher Magill, Political Conflict in East Ulster, 1920-22 – Revolution and Reprisal (2020)

John O’Mahony, Witness to Murder (2020)

Alan Parkinson, Belfast’s Unholy War: The Troubles of the 1920s, (2004)

Irish Linen Centre & Lisburn Museum

Return to Main Website